Thorium-fuelled Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs) offer a potentially safer, more efficient and a sustainable form of nuclear power. Pioneered in the US at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in the 1960s and 1970s, MSRs benefit from novel safety and operational features such as passive temperature regulation, low operating pressure and high thermal to electrical conversion efficiency.

Some MSR designs, such as the Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactor (LFTR), provide continuous online fuel reprocessing, enabling very high levels of fuel burn-up. Although MSRs can be fuelled by any fissile material, the use of abundant thorium as fuel enables breeding in the thermal spectrum, and produces only tiny quantities of plutonium and other long-lived actinides.

Current international research and development efforts are led by China, where a $350 million MSR programme has recently been launched, with a 2MW test MSR scheduled for completion by around 2020.

Smaller MSR research programmes are ongoing in France, Russia and the Czech Republic. The MSR programme at ORNL concluded that there were no insurmountable technical barriers to the development of MSRs.

Current research and development priorities include integrated demonstration of online fuel reprocessing, verification of structural materials and development of closed cycle gas

turbines for power conversion.

Thorium

Thorium is a mildly radioactive element, three times as abundant as uranium. There is

enough energy in 5000 tons of thorium to meet world energy demand for a year.

Reserves of thorium are widely dispersed around the world with large deposits in

Australia, the USA, Turkey and India. China also has substantial thorium reserves,

especially within its rare earth mineral deposits in Inner Mongolia. In Europe, Norway

has 132,000 tons of proven reserves, 5% of the world’s total3.

Thorium is not fissile and therefore cannot sustain a nuclear chain reaction on its own.

However, it is fertile, which means that if it is bombarded by neutrons from a separate

fissile driver material (Uranium-233, Uranium-235 or Plutonium-239) or from a

particle accelerator it will transmute into the fissile element Uranium-233 (U-233)

which is an excellent nuclear fuel.

The thorium fuel cycle has been successfully demonstrated in over 20 reactors

worldwide4, including the UK’s ‘Dragon’ High Temperature Gas Reactor which operated

from 1966 to 1973.

The Thorium Fuel Cycle

History of the Molten Salt Reactor (MSR)

The first Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) was constructed at Oak Ridge National Laboratory

(ORNL) in 1954 as part of the US Air Force’s nuclear propulsion programme. The

programme aimed to design and build a nuclear bomber that could fly continuously

over the Soviet Union without having to land to refuel.

The Aircraft Reactor Experiment

(ARE) resulted in a 2.5MW reactor intended to power such an aircraft. The ARE used a

molten fluoride salt as fuel (with uranium as the fissile component) and operated

successfully for 100MW-hours over a nine day period at temperatures up to 860°C.

Although the concept of a nuclear-propelled bomber was eventually abandoned, the

successful testing of this first MSR laid the research foundations for the development of

the technology for civil purposes.

From the mid-1950s under the directorship of Alvin Weinberg, ORNL began working on

thorium-fuelled MSR power station designs. Initial work focussed on one-and-a-half

fluid designs in which the fuel salt in the core contains both fissile and fertile material,

while a surrounding blanket salt contains only thorium.

As thorium is chemically similar to rare-earth fission products, it is hard to process out those fission products from the fuel salt without also removing the thorium. The early 1960s saw the

development at ORNL of two-fluid designs which sought to overcome this problem by

keeping the thorium separate from the fuel salt. To achieve this, the two-fluid designs

employed a graphite barrier between the core and blanket salts. The separation of fluids necessitated complex plumbing design involving multiple graphite tubes.

During the life of the ORNL molten salt reactor programme the plumbing design

problem was never resolved, and consequently single-fluid designs were prioritised.

The Molten Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE) which ran from 1965 to 1969 involved the

construction and successful operation of a 7.4MW reactor fuelled by molten salts

containing uranium and plutonium. The single-fluid ‘kettle’ design MSRE reactor ran

without fault for the four year life of the experiment.

ORNL research in the 1960s also produced a design for a Molten Salt Breeder Reactor

(MSBR) which would use thorium as the fertile component of the liquid fuel. The

reactor would breed its own fuel by transmuting Th-232 into fissile U-233. The MSBR

was conceived as a two-fluid design with a graphite moderator. In 1968, due to the

development of Liquid Bismuth Reductive Extraction, and in the absence of a solution

to the two-fluid plumbing problem, the two-fluid design was abandoned.

In 1972, ORNL proposed an 11-year, $350 million development and construction plan for a

demonstration MSBR. The US government’s Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) rejected

This technique enables removal of rare earth fission products without also removing thorium in single fluid systems.

The technique works more simply and effectively in two-fluid systems. After carrying out its own assessment of the MSBR which cited materials corrosion and tritium control as major technical barriers to the reactor’s development.

In January 1973, the AEC withdrew funding for the MSBR programme. Despite this, small amounts of government funding were secured for intermittent work on the MSBR

up until 1976 when the AEC finally cancelled the MSBR programme citing budget

constraints. MSR research and development at ORNL had, in fact, demonstrated that the

technical barriers cited by the AEC in their 1972 MSBR assessment could reasonably be

expected to be overcome with continued work (See Section 7).

It is likely that the ORNL MSR programme was cancelled because the US government had decided to divert all funding to the development of Liquid Metal Fast Breeder Reactors (LMFBRs)7. Work on

LMFBRs pre-dated the MSR programme and considerable government money had

already been invested in the technology. LMFBR research was taking place at numerous

government laboratories, while the MSR was the sole interest of ORNL.

A very small research program on MSRs continued beyond 1976 focussing on

proliferation-resistant designs. This period produced various designs for the Denatured

Molten Salt Reactor (DMSR) including a simplified design without fuel processing

known as the ’30 Year Once Through Design’. This design runs on low-enriched

uranium (U-235 or U-233 from thorium) unsuitable for weapons applications. The

reactor would operate over a thirty-year lifespan with no need for removal of fission

products or replacement of the graphite moderator.

The intergovernmental research and development organisation Generation IV

International Forum (GIF) helped to revive interest in MSRs in 2002 when it chose the

MSR is one of the six most promising nuclear reactor designs for future development.

Established in 2001, GIF supports designs on the basis of sustainability, safety,

economics and proliferation resistance. MSR work within GIF is led by the European

Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) and France, with Russia and the US

participating as observers. China and Japan have also taken part as temporary

observers.

Key Safety and Operational Features of MSRs

Passive Temperature Regulation – The MSR’s large negative temperature coefficient

means that regulation of the reactor’s temperature is passive. There is no need for

control rods8 or an active cooling system. The molten salt expands as a result of the

heat generated by fission, which slows the rate of fission. The reduction in fission heat

cools the salt, which in turn leads to an increase in the rate of fission.

In other words, as the reactor temperature rises, the reactivity decreases. The reactor thus automatically reduces its activity if it overheats. Conversely, if more power is required of the reactor, more heat is drawn out. The returning colder salt increases reactivity and power levels

resulting in automatic load following.

An MSR can only overheat if the circulation of the molten salt is disrupted as a result of

a loss of power, thereby preventing heat removal from the core. If that should happen,

the build-up of excess heat melts a freeze plug of solidified salt at the bottom of the

reactor, allowing the molten salt to drain into a separate tank.

Once in the tank, the fission reaction stops and the liquid fuel cools down and becomes an inert solid mass. This is an entirely passive process requiring no external power source.

Low Operating Pressure – In a Light Water Reactor (LWR), water must be kept at

high pressure10 to raise its boiling temperature. Most MSR designs operate at

temperatures between 650°C and 750°C, while molten salt boils at around 1400°C,

which means that reactor pressure remains at atmospheric levels, thus eliminating

completely the risk of a pressure explosion. With no need for large pressure vessels and

other elaborate containment structures, the cost and size of an MSR could be

substantially less than an LWR.

If the ceramic fuel pellets in a LWR melt down, gaseous fission products can be released,

and in the event of a steam explosion, these products can be carried and dispersed into

the environment by wind and water. Given the low pressure in an MSR, if molten salt

fuel should leak from the reactor, it simply spills onto the reactor room floor, where it

solidifies on contact with the ground becoming an inert mass. The fissile fuel remains

locked inside the mass and can be reused.

In a Light Water Reactor (LWR), control rods are moved in and out of the reactor core to control the level of reactivity. The rods are made of neutron-absorbing elements such as boron and hafnium. When the rods are inserted into the reactor, neutrons are absorbed and are thus prevented from splitting atoms.

This decreases the amount of fission taking place. When the rods are removed the fission reactions increase. The vast majority of nuclear power stations currently operating worldwide are Light Water Reactors (LWRs) which use solid uranium-235 (U-235) as the nuclear fuel.

10 Usually between 150 and 160 bar.

Benefits of Molten Salts

As fuel in an MSR is already in liquid form, it cannot melt down11, as solid fuel rods in a LWR can. The liquid fuel can be quickly drained from the reactor and left to cool in dump tanks.

As molten fluoride salt is heavy, it cannot be dispersed by wind. In the very unlikely

event of a terrorist attack or missile strike on the reactor, spilled fuel would only create

a small contamination zone in the immediate surroundings of the reactor.

To prevent leaching of radioactive material into soil or groundwater following a spill, MSRs can be built in protective bunkers which create an impervious barrier between any spill and

the surrounding land.

Fission products which form stable fluorides remain in the salt in the case of a leak or

accident, and in most MSR designs, insoluble or volatile fission products are

continuously removed during operation.

Molten salts are effective coolants with high heat capacity which means that

components such as pumps and heat exchangers can be compact.

Small Modular Designs Possible – MSRs can be small and modular (producing up to

300MW) which would suit power needs in remote locations, factories and military

bases. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) can be built in a central factory and assembled

on site. It is also possible to combine SMRs to form a larger power station if required. A

production line approach has the potential to generate economies of scale and result in

quick delivery of a functioning reactor.

In addition, as MSRs do not require water to operate, they can be constructed near to or

within urban areas, reducing the need for transmission infrastructure. MSRs could also

be constructed adjacent to industrial sites so that waste heat from the reactor can be

used for heat-intensive processes such as desalination, or the production of aluminium,

cement, ammonia and synthesised fuels.

A meltdown occurs when the core of a nuclear reactor overheats causing the solid fuel rods to melt and leak into other parts of the reactor. If a pressure explosion should then occur, the molten radioactive fuel (and toxic fission products) could breach all containment structures and be dispersed into the environment.

Types of MSR

Two Fluid MSRs

Interest in a two-fluid iteration of the MSBR, the LFTR, has grown over recent years

underpinned by the campaign work of Kirk Sorensen of Flibe Energy, and the

publication of popular science title ‘SuperFuel: Thorium, The Green Energy Source for

the Future’ by US journalist Richard Martin.

In 2008, a solution was proposed to the plumbing problem which led ORNL to abandon

its two-fluid designs. Nuclear physicist David Leblanc has a patent pending on an

alternative plumbing design which simplifies the complex series of graphite tubes

separating the thorium blanket from the core present in ORNL designs14.

Case Study Design: Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactor (LFTR)

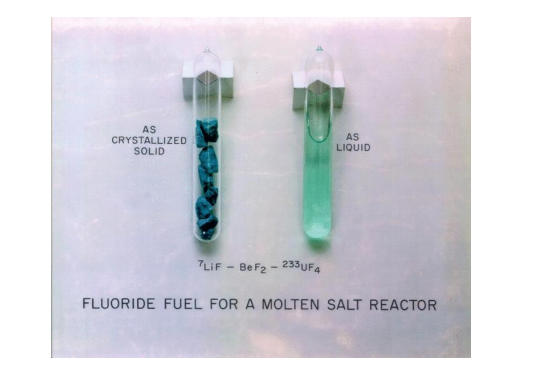

The reactor core contains fissile fuel (U-233, U-235 or Pu-239 in liquid fluoride form)

held in a graphite container which acts as a neutron moderator15. The core is

surrounded by an outer vessel, the blanket, which contains thorium dissolved in a

mixture of lithium fluoride (LiF) and beryllium fluoride (BeF2) known as FLiBe (see

Fig.4). When the fuel in the core fissions, neutrons are released which penetrate the

walls of the core and bombard the surrounding blanket of thorium causing it to

transmute into U-233. The U-233 is transferred to the core and new thorium is added

to the blanket.

The LFTR contains two separate piping loops. The first loop carries the irradiated liquid thorium into a decay tank where the U-233 can be moved to

the inner core. The second loop transfers the heated U-233 molten salt from the inner

core to the heat exchanger which drives a turbine which generates electricity. The U233 salt is then transferred back to the reactor core to continue fissioning.

The amount of fuel the reactor breeds is equal to the amount that it consumes. To keep

the fission reaction going, thorium must be added to the reactor at the same rate that it

generates and fissions uranium.

The concentration of thorium fuel in the blanket can be adjusted at any time, which

provides further control over the level of reactivity in the core.

Molten Salt Nuclear Reactor

To increase the chance that nuclear fission will take place, the speed of neutrons can be reduced so that they can be absorbed by the nuclei of a fissile material. The substance that brings about this reduction in speed is known as a neutron moderator. Common moderators include water and graphite. Molten salt itself also has a moderating effect.

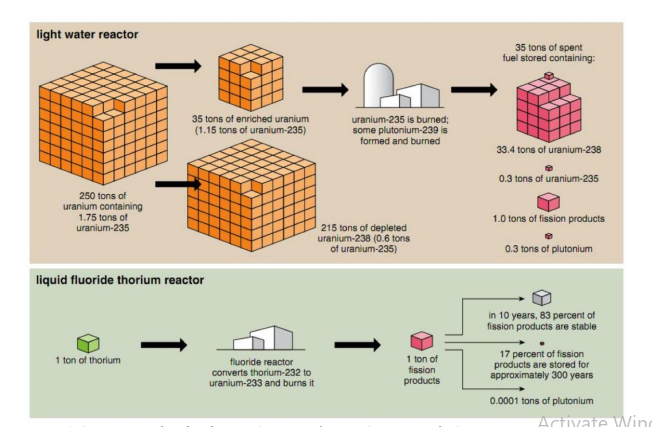

Nuclear reactors produce two kinds of radiotoxic waste – fission products16 and longlived transuranic elements17 such as plutonium. Fission products such as Xenon absorb

neutrons and slow down the fission reaction, reducing the efficiency of a reactor. After a

few years the solid fuel rods in an LWR are rendered unusable by the buildup of these

neutron absorbing fission products, thus preventing the bulk of the energy in the fuel

from being exploited. When this happens, the reactor must be shut down so that

refuelling can take place. The hazardous spent fuel from a LWR must be safely stored

for around 10,000 years.

As fission products can be removed from a LFTR during operation, the reactor can

fission almost all of its fuel including its own transuranic products. This means that

LFTRs produce almost no long-term waste and very little short-term waste, while

achieving near total burn up of the fuel. For this reason, the energy produced by one

ton of thorium in a LFTR is equivalent to that produced by 250 tons of uranium in an

LWR.

In a LFTR valuable fission products such as Xenon and Krypton gas can be removed and

sold for medical, industrial and scientific research purposes. The molten salt fluid is

pumped from the reactor into a chemical processing unit which separates the fission

When the nucleus of a fissile material undergoes fission, it splits into two smaller nuclei. These smaller nuclei are known as fission products. All elements after Uranium in the periodic table are known as transuranics, and are characterised by their instability and propensity to decay into other elements.

The small volume of fission products with no market value can be safely stored in casks, where most will become inert within 30 years. Only 17% of fission products from a LFTR have long half-lives

and these will require safe storage for up to 300 years.

Single Fluid MSRs

Single fluid MSRs combine both fertile thorium and fissile material in one salt. The two

MSRs constructed at ORNL were both single fluid systems. ORNL focussed on single

fluid systems to avoid the plumbing complexities associated with two fluid reactors.

Case Study Design: Denatured Molten Salt Reactor (DMSR) ‘30 Year

Once Through’

The DMSR was designed in the late 1970s at ORNL as part of a program to develop

proliferation-resistant reactors. Denatured fuel contains fissile fuel diluted with at least

80% U-238 which renders the fissile component unsuitable for weapons applications.

The DMSR is started from a mix of low-enriched uranium 235 and thorium contained in

a single fluid.

Neutrons in the core fission the uranium and are absorbed by the thorium. This causes the thorium to transmute into U-233, which is then fissioned. The U-238 in the core also absorbs neutrons, transmuting into fissile Pu-239.

As the DMSR was designed for simplicity without continuous fission product removal, it

does not make enough of its own fuel to self-sustain, so a fresh mixture of around 80%

U-238/20% U-235 must be continuously added to the fuel salt. The DMSR is thus

fuelled, at least partly, by uranium, but a majority of its energy would come from the

thorium to U-233 chain.

The DMSR’s graphite core is larger and thus less power dense than the earlier MSBR.

This enables the graphite moderator to last for the lifetime of the reactor18.

Gaseous fission products and noble metals are continuously removed, but the remaining

fission products are left in the molten salt for the full 30 year lifetime of the reactor. As

there is no online processing of the salt, the DMSR cannot fission all of the uranium in

the core, as the LFTR can. Despite this, the DMSR is a much more efficient burner of

uranium than an LWR.

At the end of a DMSR’s 30 year life, the salt can be removed and stored as waste,

resulting in overall uranium usage one third the size than that of a LWR. Alternatively,

the salt can be reprocessed to extract any useful uranium, before being stored, which

results in a lifetime uranium usage one sixth that of a LWR. Plutonium and other

transuranics can also be removed and recycled into the next batch of salt. This results in

a very low long-lived waste profile comparable to that achieved by breeder reactors

such as the LFTR.

Although the lack of continuous fuel processing reduces the fuel burn-up potential, it

offers the advantage of much simpler research and development requirements

compared to breeder designs such as the LFTR. ORNL believed that an operating DMSR

could be developed in 15 years19.

Graphite deteriorates as a result of neutron irradiation

The MSBR and LFTR designs require periodic replacement of graphite because of their smaller, higher power density core designs.

Thermal and Fast Spectrum Reactors

The terms ‘thermal’ and ‘fast’ refer to the speed of neutrons in a reactor. Thermal

neutrons move at around 2000m/s, while fast neutrons move at around 9000 km/s. In

the fast spectrum the fission cross-section (the probability that neutrons will fission

fissile atoms) is small. When neutrons are released from fissioning atoms they tend to

be travelling at high speed. In the same way that it would be hard to take a motorway

exit if you were travelling at 300mph, so neutrons generally do not hit the target and

split atoms when moving fast.

In the thermal spectrum, the speed of neutrons is reduced by the presence of a neutron

moderator, thus increasing the fission cross-section. Common moderators include

water, helium and graphite. Neutrons lose thermal energy when they bounce off the

nuclei of the atoms in the moderator which slows them down. This process is known as

Thermalising.

Uranium consists of fissile isotope U-235 (0.7%) and fertile isotope U-238 (99.3%).

With a thermal spectrum, even this natural uranium can support a chain reaction in

reactors such as the CANDU or Magnox, while LWRs require only modest enrichment of

3% to 5% U-235 to operate. While operating they also produce and partially burn off

Pu-239 produced when U-238 absorbs a neutron. In the thermal spectrum however,

Pu-239 is an inefficient fuel, emitting on average less than two neutrons for every one

absorbed. Conversely in a fast spectrum, while a far greater fraction of fissile material

must be present, the Pu239 produced from U238 is a far more efficient fuel and can

allow operation as a breeder where more fissile fuel is made than consumed. This is not

possible for U-238 to Pu-239 in the thermal spectrum.

20 fast reactors have been built since the 1950s, accumulating 400 reactor years of

operating experience20. However, commercial roll-out of fast reactors has yet to occur

due to technical and materials problems. The strong neutron flux in the fast spectrum

corrodes reactor materials very quickly, so the success of fast reactors will depend on

the development of new, more resilient construction materials. In addition, as it is less

likely that a fission chain reaction will occur in the fast spectrum, a fast reactor needs 3

to 4 times as much fissile material to start up than a thermal reactor, which substantially increases start-up costs.

Thorium-Fuelled Molten Salt Fast Reactors

Unlike U-238, thorium can readily be consumed in its entirety in a thermal reactor.

ORNL’s MSR work focussed only on thermal spectrum designs, and the current Chinese

MSR programme is also dedicated to thermal spectrum reactors.

FS-MSRs may eventually offer certain advantages over thermal spectrum designs. Fuel

reprocessing should be simpler in FS-MSRs as fission products do not capture neutrons

as often in the fast spectrum as in the thermal spectrum, therefore reducing the quantity

of fuel which needs to be processed. ORNL’s two-fluid MSBR design required 400 litres

a day of liquid fuel to be processed, while the fuel processing volume in the French

MSFR design is ten times less at between 10 and 40 litres a day21. With this simpler

processing requirement, the processing plant can be much smaller in an FS-MSR than in

a thermal spectrum MSR. Also, because of the absence of a moderator in FS-MSRs, the

problem of graphite deterioration is avoided.

Unlike thermal spectrum MSRs however, no FS-MSR design has ever been built, and

there are no plans anywhere in the world to build one. The current state of FS-MSR

technology development is immature23. As thorium can be fully consumed in the

thermal spectrum, there are at present few relative benefits in developing thoriumfuelled FS-MSRs. In the long term24, FS-MSRs could help expand the fissile resource

base by enabling uranium-to-plutonium breeding, as well as consuming actinides from

spent LWR fuel.

International MSR Research and Development Efforts

China

In January 2011, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) announced a 5-year

government-funded $350 million research and development (R&D) programme into

thorium-fuelled MSRs. The Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics (SINAP) is

coordinating the programme, which will be carried out at universities across China.

Two reactor designs will be developed simultaneously- a molten-salt cooled reactor

known as a Fluoride-Salt-Cooled High-Temperature Reactor (FHR), and a thorium

molten-salt fuelled and cooled reactor (TMSR). Development of the FHR is being

prioritised as the technical challenges relating to this reactor are considered easier to

resolve (see 6.1.1.). A 2MW research FHR is scheduled to be completed by around 2017.

By around 2020, a 2MW research TMSR is scheduled for completion. For both reactor

designs the intention is to follow up the 2MW research reactors with 10MW pilot

reactors, and then 100MW demonstration reactors. Funding for these larger reactors

depends upon the success of the initial 5-year programme. In the longer term, the

programme aims to build both a 1000MW FHR and a 100MW MSR demonstration

reactor in the 2030s.

The Chinese programme employs over 350 full-time staff and is the world’s only

comprehensive MSR R&D test facility, covering all aspects of MSR development

including reactor design, high-temperature molten salt loops, pyroprocessing of spent

fuel, safety and licensing, and high-temperature materials. The number of personnel

involved in the programme is projected to grow to 750 by 2015 and 1500 by 202025.

Fluoride-Salt-Cooled High-Temperature Reactor (FHR)

Both the US and China are pursuing FHR programmes and are collaborating on the

research and development effort. The US Department of Energy (DOE) started a multiuniversity research programme in January 2012 and US experts have been participating

in a design review of the Chinese FHR design. US and Chinese research teams plan to

independently develop predictive models to understand the behaviour of the Chinese

design. There are also plans for US research students to work in China on the FHR

programme. The US programme aims to develop a conceptual design for a 20MW test

reactor and a pre-conceptual design for a 200-900MW commercial prototype reactor.

Molten-salt cooled reactors enjoy some of the safety and operational benefits associated

with molten-salt fuelled reactors. As FHRs run at atmospheric pressure, large pressure

vessels are not required and unlike water-cooled reactors, there is no steam in the core

which eliminates the risk of a pressure explosion. High operating temperatures mean

that FHRs, like MSRs, can make use of efficient Brayton cycle gas power conversion. The

high heat capacity of the molten-salt coolant means that the reactor can be compact and

relatively cheap to construct.

In the pebble-bed FHRs favoured by the Chinese, the fissile fuel is contained within golf

ball size pebbles, known as tristructural-isotropic (TRISO) fuel. The pebbles consist of a

fissile fuel kernel surrounded by four layers of carbon and ceramic material. The layers

retain fission products within the pebble and enable the pebble to withstand high

temperatures without cracking, thus avoiding the possibility of meltdown. The pebbles

are immersed in the molten salt coolant and move slowly upwards through the core.

When they reach the top they are removed. If fissile fuel remains in them, they are

reinserted at the bottom of the core. If they are spent, then they are transferred to

secure storage facilities, and fresh replacement pebbles are inserted into the core.

Operational experience with TRISO fuel has been developed over the past 20 years in

Germany, China and the US. Production of TRISO fuel already takes place in China to

fuel prototype high temperature reactors at Tsinghua University26.

Given the relatively advanced state of FHR development, the US and Chinese research

programs believe that FHRs will be commercially ready sooner than MSRs, perhaps

within 20 years, and therefore priority is being given to FHR work, hence the projected

three-year gap between the 2MW Chinese test FHR and the subsequent test MSR. The

development of FHRs will benefit MSR development, as the R&D work on high

temperature salt systems and the Brayton power conversion cycle is equally applicable

to MSRs and represents about half of the R&D challenges relating to the development of

the MSR.

6.2. France

The French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) has funded a molten salt

reactor programme at its Grenoble-based Laboratory of Subatomic Physics and

Cosmology (LPSC) since 1997. The LPSC has developed a conceptual 3000MWth fastspectrum MSR design known as the Molten Salt Fast Reactor (MSFR). The MSFR is a

two-fluid core and blanket design, which can be started with an initial fissile load of

U233, U235 of Pu239. The fast neutron spectrum allows unprocessed transuranics to

be used as fuel, and reduces the daily fuel salt reprocessing volume to around 40 litres,

as opposed to 400 litres in a LFTR, thus requiring only a small reprocessing structure.

The design also ensures a strongly negative temperature coefficient, a feature integral

to MSRs but found by the LPSC not to be present in ORNL’s MSBR design.

In 2008, the Generation IV International Forum (GIF)27 chose the MSFR as their default

MSR concept. Work on the MSFR has also received EU funding through the Evaluation

and Viability of Liquid Fuel Fast Reactor Systems project (EVOL). The objective of EVOL

is to produce a more detailed MSFR design by the end of 2013.

Czech Republic

The Czech government has funded MSR research at the Nuclear Research Institute Rez

(NRI Rez), just north of Prague, since 1997. Between 1997 and 2003, NRI Rez’s SPHINX

(SPent Hot fuel Incinerator by Neutron fluX) project focussed on a conceptual design for

a Molten Salt Transmuter Reactor (MSTR) fuelled by plutonium and minor actinides

recovered from spent LWR fuel.

From 2004 to 2008 the SPHINX project produced a conceptual, fast spectrum, thoriumfuelled MSR breeder design, with accompanying research covering theoretical and

experimental work in materials, fuel cycle chemistry and molten salt thermohydraulics.

SPHINX produced a new nickel alloy to replace Hastelloy-N, known as SKODA-MONICR.

A separate project running from 2006 to 2011 covered reprocessing issues such as

flouride separation processes relating to the thorium-uranium fuel cycle and the

separation of transuranics.

In September 2011, the US Department of Energy (DOE) announced a bilateral US-Czech

nuclear research and development programme. The programme includes work on

molten salt coolant. Coolant salt originating from ORNL is being tested at the Czech

nuclear test facility at Rez. To contribute towards the joint effort, a consortium of Czech

companies and institutions including NRI Rez are pursuing a three-year R&D project

(ending 2015) into FHRs and MSRs, covering theoretical and experimental activities in

reactor physics, fuel cycle processes, molten salt thermohydraulics and structural

material development.

Russia

Russia’s National Research Centre, the Kurchatov Institute, is pursuing the Minor

Actinides Recycling in Salts (MARS) project, planned to run until the end of 201428. The

MARS team have developed the conceptual Molten Salt Actinide Recycler and

Transmuter (MOSART). This is a non-moderated, fast spectrum design using plutonium

and minor actinides from spent LWR fuel as fuel to produce 2400MWt. It uses a sodium-

27 GIF is an international project to coordinate research and development efforts on advanced nuclear reactor designs.

28 MARs project funding for the period 2010 to 2012 amounted to 35 million rubles, equivalent to around $400,000 a year.

Lithium-beryllium fluoride salt chosen for its high solubility for actinides. MOSART has a

peak operating temperature of 720°C.

A second design using thorium as fuel is being worked on. The Hybrid MOSART system

is a fast spectrum two-fluid core and blanket reactor which would convert thorium into

U-233 either to generate electricity directly, or to be extracted and used as fuel in an

MSFR, as per the French design.

In 2011, the MOSART project team carried out studies on a variety of molten salt

mixtures, as well as corrosion testing of nickel-based alloys29. The team has developed

a nickel-molybdenum alloy known as HN80MTY which has withstood tellurium

corrosion at temperatures up to 740°C. The team believe that HN80MTY has resolved

the corrosion problems associated with Hastelloy-N and that the alloy’s ‘corrosion and

mechanical properties completely meet MOSART requirements’30.

MSR R&D Priorities

Continuous Processing of the Fuel Salt

In order for a closed-cycle MSR such as the LFTR to successfully breed U-233, the fuel

salt must be continuously processed to remove neutron-poisoning fission products. In

addition, the U-233 produced must be separated from the blanket salt and transferred

to the fuel salt. Towards the end of the MSR programme, ORNL recognised that they

had much work still to do to demonstrate a continuous fuel processing system. Only

small-scale experiments had been carried out and component development was still at

an early stage. ORNL had, however, found ‘no insurmountable obstacles’ to progress in

this area.

ORNL had shown that U-233 separation could be achieved through a process known as

fluorine volatility. The newly-created U-233 is transferred to a fluorinator where it is

exposed to fluorine gas to form uranium fluoride which is then converted into a gas.

This gas is exposed to hydrogen which converts the U-233 into a soluble form, after

which is transported to the fuel salt. This process was demonstrated during the

MSRE, though ORNL made clear that further testing would need to be done to

demonstrate fluorination on a continuous basis.

Successful fission product removal experiments were also carried out at ORNL, but

continuous extraction of fission products was not demonstrated. Xenon and Krypton

gas are produced by the fission reaction, and if they are not removed from the reactor

then they absorb neutrons which slows and eventually stops the chain reaction from

taking place. The MSRE showed that both gases can be removed from the system by

injecting helium into the salt, which absorbs the gases, and is then itself removed from

the salt along with the trapped neutron poisoning gases. This process is known as

Sparging.

Rare-earth fission products were successfully removed from molten salt in multiple

experiments at ORNL using the metal transfer method known as liquid bismuth

reductive extraction33. However, no large-scale testing was done. ORNL recognised that

‘sound engineering tests of individual process steps’ and ‘relatively long-term and near

full-scale integrated tests of the [reprocessing] system as a whole’ would be necessary

for future development of MSR technology34. ORNL believed that the fuel processing

system could be demonstrated within 15 years.

Recent developments in electrochemical processing of molten salt fuel could provide

new techniques to aid development of MSR fuel processing. Electroseparation methods

such as anodic dissolution and cathodic deposition are being tested at the Nuclear

Institute Rez in the Czech Republic. These methods may provide a means to separate

lanthanides from actinides, so that actinides can be fed back into the core for

fissioning, while lanthanides are removed and stored as waste.

An additional challenge for the R&D effort relating to fuel processing is the form in

which waste fission products will be stored. At present there is no proven process

available to convert fluoride High-Level Waste (HLW) into a form suitable for safe

storage. Potential methods are being developed to solve this problem involving both

vitrification and crystallisation of the liquid waste.

Materials/Corrosion

When Oak Ridge MSR research funding was curtailed in 1973, one explanation given by

the AEC was that corrosion in reactor materials presented a major technical difficulty

for further MSR development. In fact, ORNL studies had demonstrated that the

material of construction, nickel-based alloy Hastelloy N, had ‘generally performed very

well’. ORNL did encounter two problems with Hastelloy N for which likely solutions

were found, though not fully tested.

Radiation Damage – Hastelloy N corrosion occurred during the MSRE as a result of

neutron irradiation. When neutrons react with boron and nickel contained within the

alloy, helium gas is produced which builds up and stresses the alloy, causing it to

become brittle. Later Oak Ridge work showed that adding titanium to Hastelloy-N

enables the alloy to withstand radiation much more effectively41. Extensive tests of the

new alloy were cut short by the 1973 funding cut to the MSR programme.

Tellurium – The MSRE also established that the fission product tellurium corrodes

Hastelloy N, causing cracking along the grains of the alloy. Oak Ridge later found that

adding the soft metal niobium to the alloy reduced tellurium corrosion, though the

studies were not carried out over long enough a period to conclusively demonstrate

that the addition of niobium completely resolves the corrosion problem.

Oak Ridge found that an alternative approach to the tellurium problem, controlling the

oxidation potential of the salt, was also effective in reducing corrosion43. Combining this

approach with a titanium-enriched Hastelloy N could resolve the corrosion problem

Completely.

New Materials – Materials developed since the end of the ORNL MSR programme offer

innovative ways of resolving difficulties with corrosion in MSRs, and could replace

Hastelloy N and other nickel-based alloys as the main construction material for MSRs.

New materials could also allow for higher operating temperatures, perhaps up to

1000°C. Higher temperatures would improve thermal to electrical conversion efficiency

and enable process heat applications such as hydrogen and liquid fuel production.

Carbon fibre-reinforced carbon, also known as carbon-carbon (C/C), is a composite

consisting of graphite reinforced with carbon fibre, and is already being developed for

use in high-temperature reactors. C/C maintains its strength at temperatures up to

1400°C and is compatible with molten fluoride salts. This opens up the possibility of

constructing MSR heat exchangers, pumps, piping and vessels out of carbon-carbon.

Technical challenges remain for carbon-carbons in high temperature nuclear

applications. In very high temperature reactors (>1000°C), C/C may degrade when

subjected to core level radiation, and, unlike metal alloys, C/C is potentially permeable,

so composites with very low levels of permeability will need to be developed.

Silicon Carbide (SiC) is also a promising material for future high temperature nuclear

applications. SiC has very high temperature and radiation tolerance44 and can prevent

oxidation in carbon-carbon if used as a coating. A SiC composite comprising silicon

carbide fibre and silicon carbide matrix (Sic-Sic) could compete with C/C as a

standalone material for high-temperature reactor components. SiC is already used in

TRISO fuel.

Both Sic-Sic and C/C require the development of suitable joining technologies.

Advances in laser joining could prove the solution45. The Chinese MSR programme is

currently testing C/C and Sic-Sic composites up to temperatures of 1000°C46.

Buildup of Noble Metals

Noble metals formed as fission products do not dissolve in molten salt, and instead are

deposited on the surfaces of components within the reactor. They produce large

43 ORNL, ‘Status of Tellurium-Hastelloy-N Studies in Molten Fluoride Salts’, October 1977.

44 Ozawa et al, ‘Evaluation of Damage Tolerance of Advanced Sic/Sic Composites after Neutron Irradiation’, amounts of decay heat which can damage the heat exchanger. Noble metals need to be

captured for an MSR to operate successfully.

These metals tend to accumulate on metal surfaces, so heat exchangers constructed

from new materials such as carbon-carbon composites may be able to avoid harmful

build up. Buildup can be encouraged in less problematic areas of a reactor, such as the

salt clean-up system, by using coated carbon-foam matrices which absorb the noble

metals. Research into the noble metal problem in molten salts was, until recently, an

expensive undertaking, involving a test reactor or radioactive salt loop. The French

national Laboratory of Subatomic Physics and Cosmology at Grenoble have developed

cheaper non-radioactive test methods for molten salts, which will enable faster

progress in resolving the noble metal problem.

Tritium Control

Tritium is a radioactive hydrogen isotope which is produced in significant quantities in

MSRs as a fission product and also as a result of neutrons reacting with lithium in the

fuel salt. Small quantities are routinely and safely released into the environment every

day from existing nuclear power plants. However, in sufficient quantity, tritium can be

hazardous to human health, so its release from nuclear power stations must be

controlled. National nuclear safety bodies set limits on the amount of tritium that can

be released into the environment.

At high temperatures in an MSR, tritium can pass through metal walls and potentially

enter the power cycle, increasing the risk of uncontrolled release into the environment.

To prevent this, tritium needs to be captured and isolated. The Oak Ridge MSR designs

assumed a steam power cycle. Tritium reacts with steam to form tritiated water, and

separating the tritiated water from non-tritiated water is complex. ORNL experiments

demonstrated that tritium could be trapped in the secondary coolant if that coolant

contained sodium fluoroborate. Later analysis has suggested that this would be a

difficult and expensive option for isolating large quantities of tritium.

Alternative power cycles, such as the Brayton cycle, could offer the solution. Tritium

can be trapped in and removed from gas in the Brayton cycle. Removal of tritium from

helium gas has already been demonstrated cost-effectively in helium-cooled hightemperature reactors.

Power Conversion Systems

During the ORNL MSR programme, the Rankine steam cycle was the only proven

method of converting heat to electricity. The steam cycle presented a number of

technical challenges to MSR development including chemical reactivity of molten salts

and water, the risk of salt coolant freezing because of the relatively low temperature of

the steam cycle, and the tritium problem (see above 7.4).

The Brayton gas cycle, commonly used in jet engines, offers multiple potential

advantages to the steam cycle in MSR applications. Tritium can be removed in the

Brayton Cycle, and due to its high temperature operation, the Brayton Cycle also

protects against the freezing of molten salt coolant. When coupled with a reactor outlet

temperature higher than 700°C, Brayton also offers much greater conversion efficiency

of thermal to electrical energy.

In an MSR attached to a combined or closed-cycle gas turbine (CCGT), heat is

transferred from the molten salt coolant to gases such as helium, nitrogen, carbon

dioxide or compressed air. The heated gas then drives a turbine which generates

electricity. While steam cycle temperatures peak at around 550°C, gas cycles can

operate above 1000°C. MSRs can produce outlet temperatures in excess of 650°C, with

the heat transfer capacity of molten salt increases with higher outlet temperatures.

Therefore the combination of a high-temperature MSR and high-temperature CCGT

maximises potential power conversion efficiency. CCGTs can be 50% more efficient than

steam cycle turbines.

CCGTs have not yet been proven at a scale suitable for a power plant, though small-scale

CCGTs have been successfully demonstrated, and large-scale prototypes are currently

being built. The FHR programs in China and the US (see above 6.1.1.) plan to bring

FHRs with CCGTs to commercial level in 20 years. The US FHR program has opted to

develop an air-Brayton combined-cycle system which enables process heat production,

grid stabilisation and base-load and peak electricity output. These features may enable

significant cost savings compared to current LWRs.