Deep in the vaults of the UK National Archives at Kew, South West London, lie a series of extraordinary documents which few have examined since they were composed in the 1960s and 1970s. Now declassified, the documents are the remaining records of Britain’s Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) programme, relics of a time when nuclear fission R&D; was considered a priority by the British government.

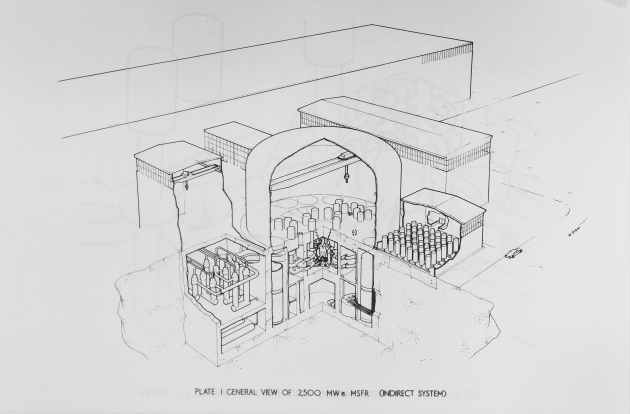

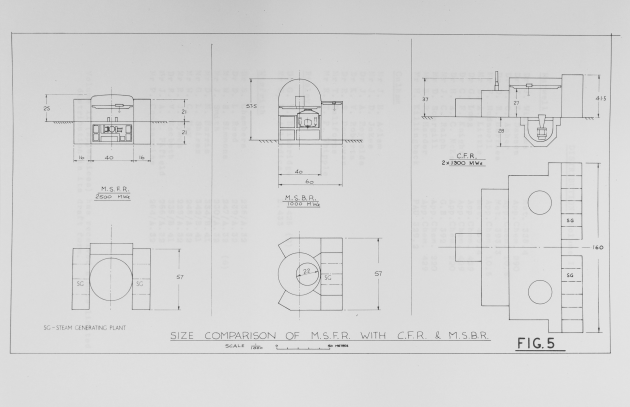

While Alvin Weinberg’s more famous Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) MSR work progressed in the US, the documents reveal that Britain’s Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) were developing an alternative MSR design across its National Laboratories at Harwell, Culham, Risley and Winfrith. AERE decided that there would be little to gain from replicating ORNL’s work, so they opted to focus on a lead-cooled 2.5GWe Molten Salt Fast Reactor (MSFR) concept using a chloride salt, as opposed to ORNL’s thermal spectrum Molten Salt Breeder Reactor (MSBR) which employed a fluoride salt.

The UK MSFR would be fuelled by plutonium, a fuel considered to be ‘free’ by the programme’s research scientists, who viewed the UK’s plutonium stockpiles as an asset rather than a liability. Despite developing quite different designs, ORNL and AERE seem to have had close contact during this period with information exchange and expert visits taking place across the pond. Theoretical work on the concept was conducted between 1964 and 1966, and experimental work was ongoing between 1968 and 1973.

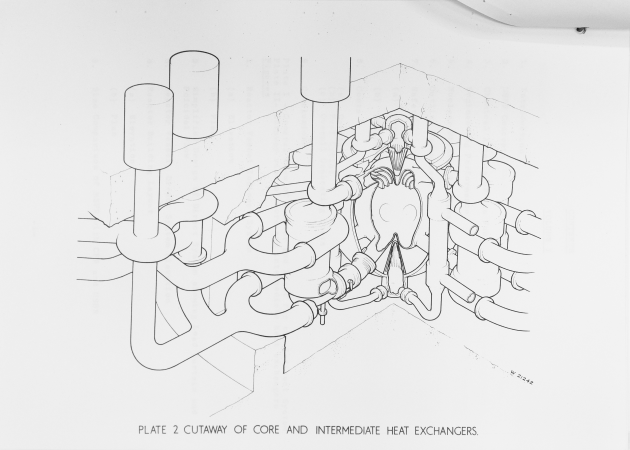

Extensive experiments on molten salt fluid dynamics were undertaken in large test rigs, the results of which are compiled in the documents. Substantial work was also carried out on heat exchanger design and the lead coolant system. The programme appears to have been receiving government funding of around £2-3 million annually. Correspondence between senior programme researchers reveals that the programme came to an end in 1974 when the government withdrew funding, in part as a response to the 1973 cancellation of ORNL’s MSBR work, and in part because the Prototype Fast Reactor at Dounreay, which went critical in 1974, was considered the priority for funding. Tantalisingly, the documents show that in 1975 AERE were approached by Swiss and French nuclear researchers to form a joint European MSR programme.

Without domestic funding in place, Britain was unable to join, leaving us to wonder about what might have been. While it’s disappointing to see that the UK MSR programme ran aground after going so far, it’s also inspiring to learn about the level of commitment backed up with resources that enabled this work to be carried out over a ten year period. The documents are a sobering reminder of how much we’ve lost in the UK in terms of advanced fission expertise and political will. The scale of the 2.5GWe MSFR, equivalent in output to two Sizewell Bs, demonstrates the huge ambition of the project.

If the programme had continued and a commercial MSFR had started supplying the grid in 1995, removing the need for 2.5GWe of coal-fired power, this would have prevented 340 million tonnes of CO2 emissions — or nearly three quarters of the UK’s entire annual CO2 emissions in 2013. A single MSFR would have reduced UK carbon emissions by approximately 5% a year, every year, since 1995!

A fleet of six MSFRs could have completely replaced coal in the UK’s energy mix. The National Archives contain all of the experimental data and research findings. Despite this reactor’s role in reducing carbon and eliminating plutonium, those research papers gather dust. The relevant authorities must digitise and make freely available these papers, as soon as possible.

There is always hope that the UK MSFR work was not completed in vain. Current reactor programmes freely mine the work of the “golden age” of nuclear innovation in the ’60s and ’70s. For instance, the promising U-Battery reactor, designed by Anglo-Dutch company Urenco, is a modern iteration of the Dragon Reactor, designed, built and operated at Winfrith in the 1960s.

The Chinese MSR programme has extensively mined the treasure trove of research findings accumulated during ORNL’s 1960s MSR programme. Could a 21st century nuclear innovator make use of the UK MSR programme data, breathing new life into Britain’s forgotten molten salt reactor?

UK MSFR – Cutaway of Core and Intermediate Heat Exchangers. UK National Archives.

UK MSFR – Size Comparison with CFR & MSBR. UK National Archives.

The AWF is presently in the process of digitising the MSFR papers, which we hope to release for public benefit. This is a time-consuming process, so please bear with us. The physical AERE MSFR papers are accessible to all, for free, at the National Archives, Kew. Search the National Archives at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.